This is the second episode in our journey

In a recent article, I tell the story of how the 4-day week went from a joke to an actual project at my company, resolution.

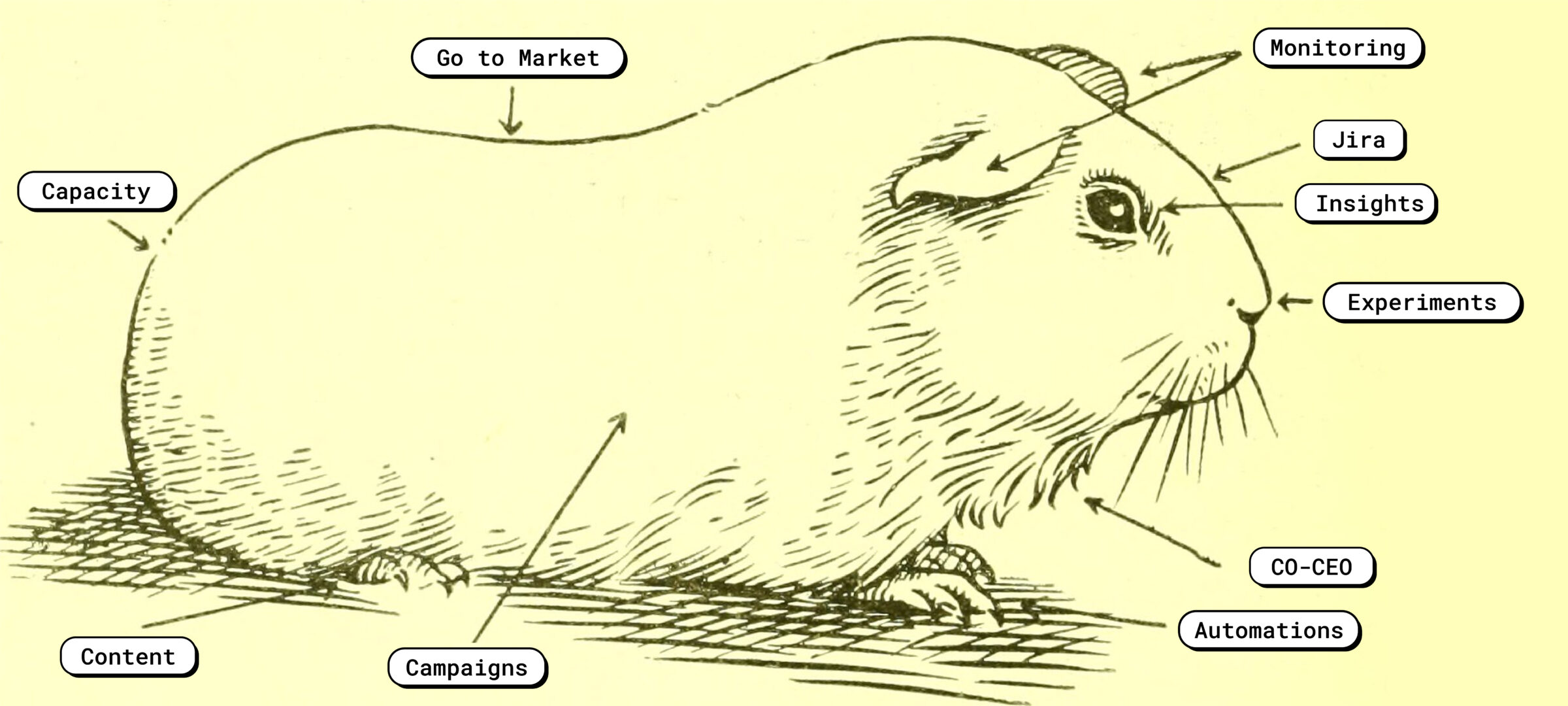

In this article, I zoom into the marketing team as we prepared for the experiment, changed our organization and team workflows and transformed from an autonomous (and somewhat chaotic) team that didn’t work too much with Jira into a fully-fledged agile crew.

The endemic disease of internal marketing teams

The Marketing Guinea pig was arguably the sickest patient. That’s why we were the first to race towards a horizon where nothing terrible would happen if we only worked 4 days per week.

We’re not surgeons. Nothing is going to happen if our tasks get delayed for a couple of hours

Björn Döhler, Co-CEO and Sales & Marketing Team Lead

After all, running an efficient marketing team at a company like ours is inherently challenging because of our business model and the structure of the company.

So let’s start with that.

Marketing teams are naturally inclined to dispersion

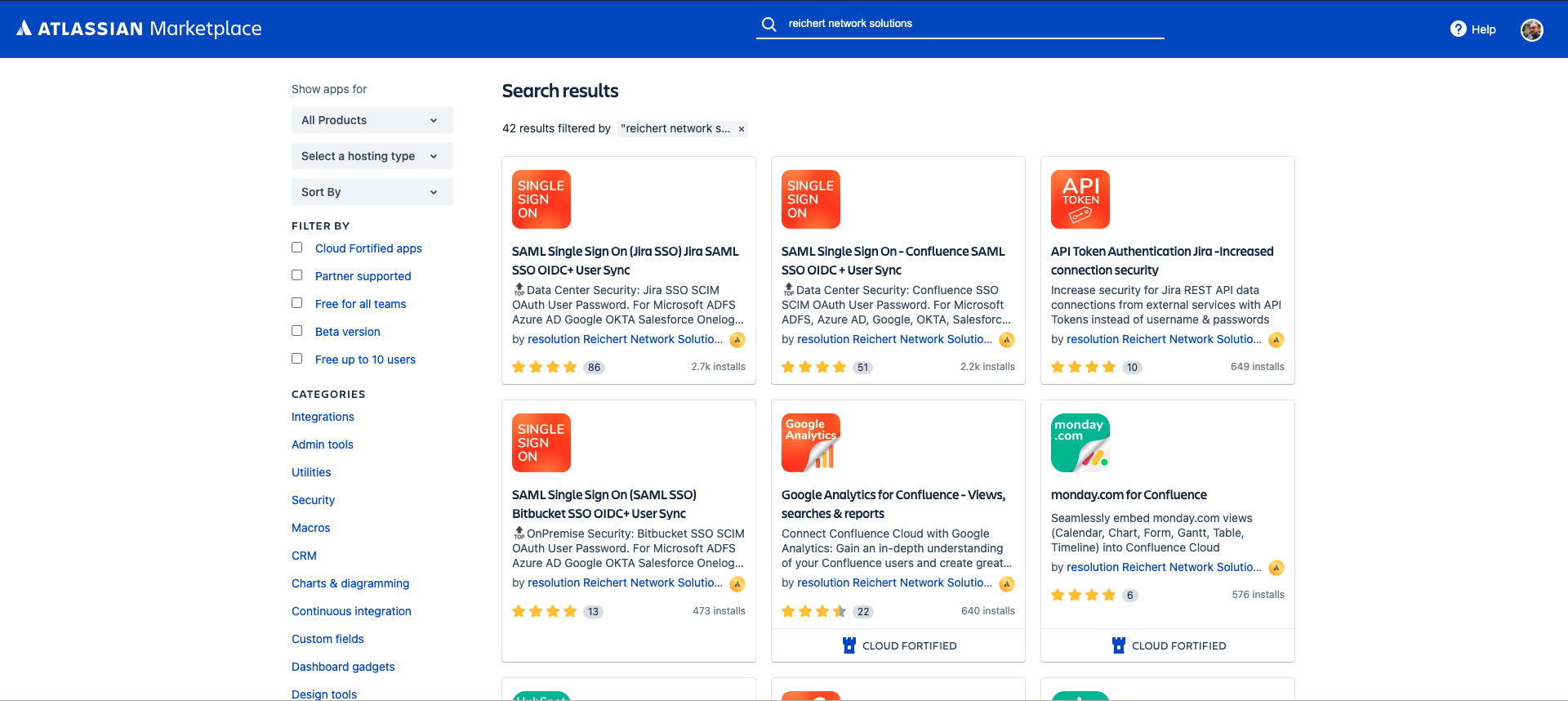

Before we know what works well, we need to try new channels, formats, and campaign layouts. Unfortunately, the scale of our audience (a niche within the Atlassian user base) means that experiments are often inconclusive or hard to replicate. We do have some serious playbooks that have worked well for us, but we’re perfectly aware that consumer behavior changes all the time and we can’t hope to make new apps successful with the same Go to Market that has been used for SAML SSO since 2013.

Marketing activities are only loosely tied to revenue

Resolution has no sales team. So marketing doesn’t really generate marketing leads to pass them along to SDRs, as many other companies do. Perks of being an Atlassian Marketplace Partner!

We go nowhere near the attribution game. Instead, we see marketing as a component of the product lifecycle, measure which campaigns are more effective, and make sure that we keep pushing the products with the highest potential.

We’re swimming in the innovator’s dilemma

If you’ve read the classic business book The Innovator’s Dilemma, you may remember that corporations which created innovation spinoffs with their own teams, structures and incentives were more capable of innovating on time and surviving disruption than those which simply persisted in improving their high-end products for their better paying customers.

Rather than continually working to convince and remind everyone that the small, disruptive technology might someday be significant or that it is at least strategically important, large companies should seek to embed the project in an organization that is small enough to be motivated by the opportunity offered by a disruptive technology in its early years.

Clayton M. Christensen, The Innovator’s Dilemma

We’ve learned from this lesson, with nuances. A corporation can afford to create a separated spin off. We can afford to create a separate cloud department, but we won’t create two different marketing teams.

And since our legacy products still contribute to revenue in excess of Pareto’s law, as marketers we have the constant need to strike the balance between defending our User Management stronghold and creating content, campaigns, and marketing experiences for the smaller cloud apps, each of them with their own story, benefits, and specific audiences.

Our in-house marketing departments support everybody else in the company

Supporting two development teams and their output may not sound like a lot. It does look a bit less balanced when you think that a team of 8 does marketing for almost 40 plugins. We have so many different apps with different focus, storylines, and audiences that supporting them efficiently would keep busy two or three teams our size.

Each of us is autonomous

We’re a team of senior marketers with close to 0 micromanagement. In stand-ups, we basically inform the rest of the team of what we’re doing, and ask for help if we need it. Of course, we do agree as a team on which types of campaigns we want to pursue, but almost every execution detail is delegated.

The painful mutation from one-man band to full orchestra

Besides these structural factors, the marketing team had also grown enormously in three years, going from a single team member in 2019 to a size of 8. This process also involved losing some of the initial team members, regrouping to redefine our areas of specialization, and essentially making sure that we had clear responsibilities so that we wouldn’t have blind angles or do double work.

The business feels the road bumps

Together with overlapping paternity leaves from some of us (including me!), this necessary restructuring made us lose speed for about half a year, coming up to a point where some of us noticed that the rest of the company was out of touch with our marketing efforts.

It was a sobering realization. We had handed out the instruments in the orchestra, but we weren’t playing a very convincing tune together… yet.

Drowning in freedom

Every marketing team member was deciding autonomously what they would be doing on any given day. We worked off our standup conversations and our notes, scattered in Jira, post its, Confluence personal spaces… Making dozens of such autonomous decisions every day was extremely difficult. And it was also wrong. It took us precious time and often left us wondering: Am I doing the right thing, or am I forgetting something important?

Since we weren’t tracking all our work in Jira, every time something happened that made us park ongoing tasks, we risked have to restart all over again whenever we wanted to pick it up. The growth of our product portfolio was eating up our productivity, and we were drowning in our freedom.

The solution lies in the Atlassian stack

The main enemy was clear: distraction. But there was something we could do against it. In fact, we were already working on it.

Jira Work Management had exciting early approaches and we planned with that. But it’s always the same: what happens first with a plan? It changes. You have to internalize that.

Björn Döhler

We needed to restrict our movements, to offer better guidance on the things we wanted to do and the things that we would not do. And we needed to cut down on the number of key initiatives that we wanted to deliver so we could all make room for them.

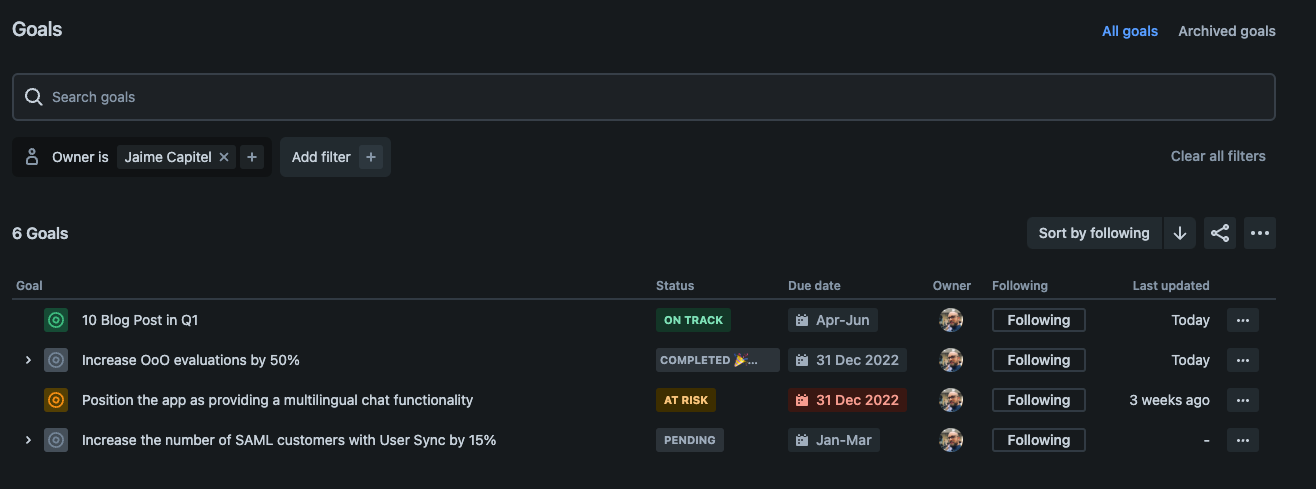

First, Atlas Goals to fight against the monster of distraction

At some point Björn Döhler, our team lead and Sales and Marketing Co-CEO, suggested a light approach to OKRs, and decided to test a new Atlassian product, Atlas, to maintain it.

That’s how in May 2022 we adopted quarterly goals, which have since mandated which products and initiatives deserve our attention… and which are parked. We already knew in general terms what was the strategy of the company and tried to align to it. Quarterly goals were a step in the right direction: they were more tactical than our general strategy, and protected work on top priority products, while still permitting to do “maintenance work” in other areas.

To be honest, we’re still using Atlas, but our process is so simple and our organization so small that we could use a simple Confluence page for tracking our goals.

Then, the 4-day week accelerated change

When the entire company met in June 2022 we had only started testing the goals system, and the experience was positive overall. We felt more motivated, and were deliberately planning high-impact actions. The decision to test a 4-day week and the resolution to change the way we work arrived at a moment in which we were already looking at ourselves in the mirror and trying to become more effective.

In perfect contrast to the skeptics and critics that believe a 4-day week will harm business results, our marketing journey was timed to tell a different story. A 4-day workweek can improve collaboration and organization simply because it can motivate teams to commit to radical changes in behavior that would otherwise be unrealistic.

Actually, our dev colleagues had tried Scrum

Marketing wasn’t the first team playing with Scrum. The model had been tested in 2017, but it didn’t work out.

My colleague Olli had already worked with Scrum at previous companies, and knew that adopting the framework is easier said than done.

I think the main problems in the other companies where I’ve seen this happen were that either the process wasn’t fully implemented (“we’re doing standups now and everything is fine, we don’t even need all the other meetings”) or, in another case, that the team didn’t fully accept the process because it was imposed from above, so some team members didn’t take it seriously and more or less worked against it. This made it harder for the whole team to follow the process.

Nobody at resolution was too naive about the preparation. We knew that every team needed a workflow that they could choose to love (I’ve actually borrowed this expression from a fitness coach and ex-marine who inspired us with the paradoxical “everyone hates burpees. I choose to love them”), and that aligning each individual in a team to a process wouldn’t be an easy task.

The magic: Working with Sprints in Jira

The quarterly goals gave us a frame of reference for planning campaigns in the mid term. But we still were missing solid foundations:

- we had to start measuring our productivity if we wanted to be able to determine whether the 4-day week would make a dent in our output.

- we still needed proper upfront planning to connect long-term strategy to tactical activities

After talking to Chris to weigh our options, Björn suggested that the team tried out our own version of Scrum. The team accepted the recommendation, and we immediately moved away from our marketing project with calendars and timelines in Jira Work Management to a Jira Software project for agile teams.

Sprints had an immediate boost on morale

The effect on the team morale was immediate with only one or two sprints. And we still hadn’t figured out the planning piece!

Increased focus

We felt that, by committing to completing a limited amount of tasks for the duration of the sprint, we always knew where to put our effort. We were not improvising anymore.

Everything is in Jira

After recording tasks that would take longer than 5 minutes in Jira, we would end up with hundreds of issues that still contained very little information in them.

Fabia, our process manager, would then scold us and friendly remind us to please include full descriptions and the occasional updates.

Cut the waste

We have drastically reduced the amount of initiatives that we drop mid-way, simply because it’s easier to swallow up more of them and run them in parallel through the sprints.

Story points are the answer to the productivity question

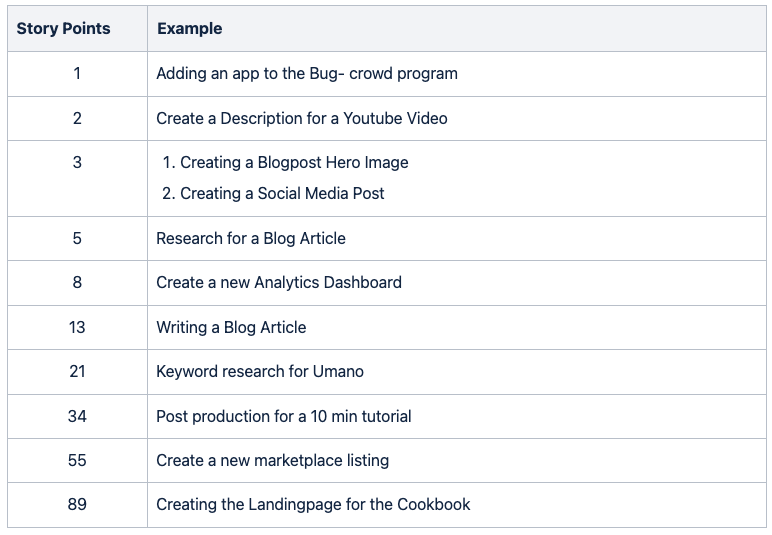

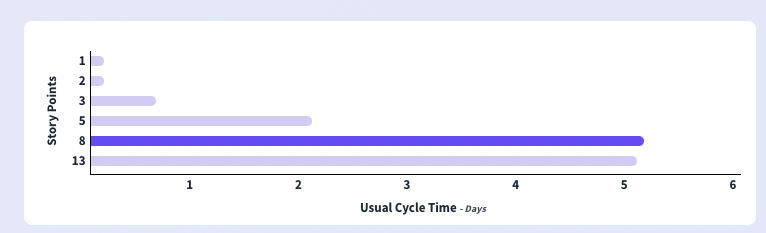

The Cycle Time in which we complete Jira tasks is proportional to the number of story points… with some exceptions for the larger tasks.

Once sprints were implemented, we only needed to decide on a productivity unit. We went with story points, since we don’t believe in time tracking!

We don’t use story points to predict when any specific task would be completed, to plan our deadlines accordingly, or to measure whether individual performance meets expectations.

The whole point of using story points is to have a reasonable measure of our output as a team, and to make sure that we reach a predictable velocity that helps in committing to our plans and ultimately delivering them.

The many Scrum pieces that we dropped

The transition was neither obvious nor painless. Not every team member was equally aware of what it meant to work in sprints. And there were many elements in the Scrum methodology that we had to get rid of:

- No Scrum roles. We don’t have a Scrum Master and a Product Owner, just as there is no Development Team.

- No unitary goal. We don’t have a common goal to be delivered at the end of the sprint, since we concurrently work towards at least three or four different apps at the same time.

- No rituals. Since we’re not crafting a unitary product, we decided not to adopt most Scrum ceremonies like backlog grooming, retrospective, or sprint planning.

What we adopted

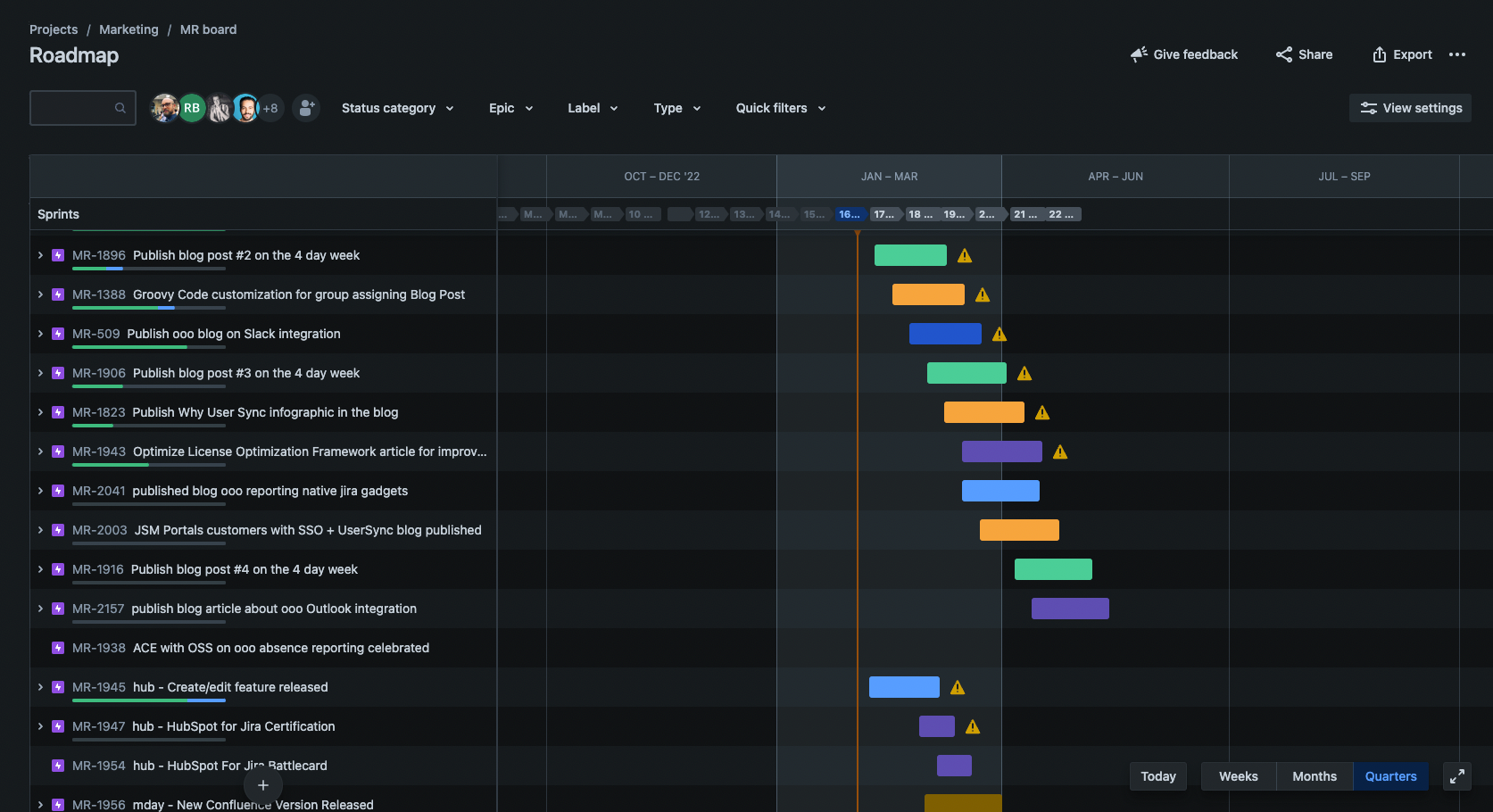

Our Marketing roadmap contains so many epics that powerful filtering has become the strongest requirement

In the end, our model of Scrum consists of basically three elements:

- Sprints. We plan our work in bi-weekly sprints. We may have to respond to external requests, but we try not to start any additional actions proactively.

- Story points. We have adopted the Fibonacci scale, with most tasks being 3, 5, or 8 story points.

- Epics. Epics capture our marketing campaigns, and should be aligned to any initiative that impacts customers.

These three elements support each other in everything we do. Epics are the glue that holds together our planning. The decisions of what epics to work on stems from quarterly goals, and their content fill out the sprints. How many tasks fit into each sprint is something we estimate using story points.

The tracky ending: story points and efficiency rate

After 5 or 6 sprints, as the Summer holidays were passed behind our backs, we had a realistic idea of our average output: 450 story points per sprint.

Getting estimations right took some practice. We once did a poker planning session to have a feeling of whether our estimations were comparable. The exercise was quite useful, because seeing the estimations of our colleagues quickly made us come together.

We also discovered some funny misconceptions: one of us assigned 81 story points to a hotel reservation thinking that the consequence of not completing the task would imply sleeping on a bench in the street!

Overtime we’ve gotten better at estimating the complexity of a task.

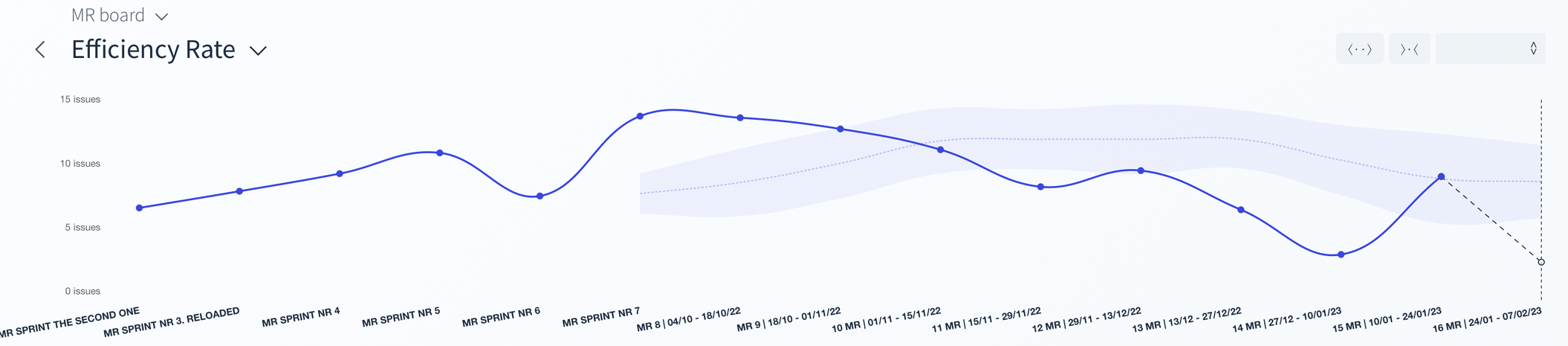

But there’s a second measure of our productivity: the efficiency rate, which tells us the average number of issues completed per person. We use this indicator in combination with the knowledge of the holiday season, vacations, and other distractions.

Challenges still ahead

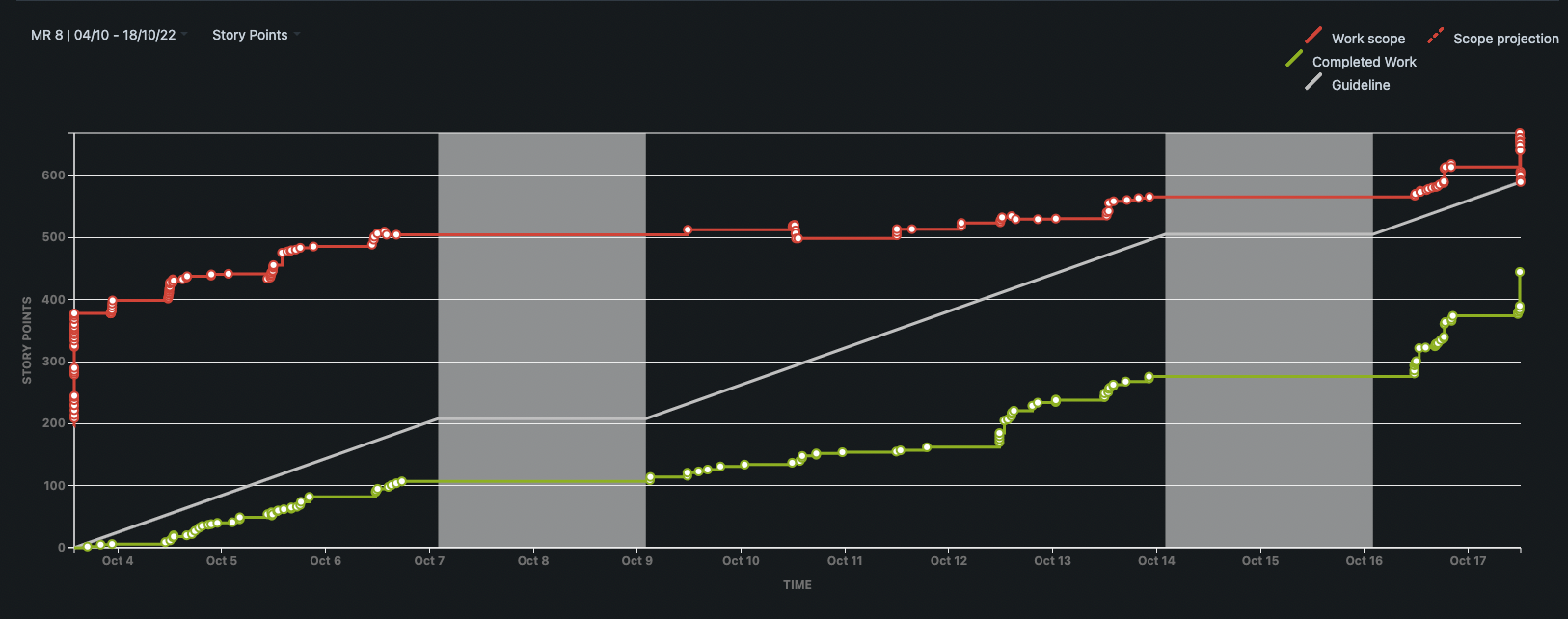

We’ve come a long way, yet we have barely started. All in all, the burnup chart of our sprints in Jira still looks like an upstream river, where the gap between work scope and completed work never closes.

Planning and committing

We keep committing way too much work to the sprints and having scope creeps. Judging by how committed and completed work grow in parallel, it seems like some of us work like this:

- We finish a task and realize there’s a connected task that we would have to complete next. But that task either doesn’t exist or is still sitting in the backlog

- We finish a task and move to something

We know that we can’t plan every bit of work. There will be surprises, business requests, and event invitations that hits us. Telling apart overcommitment from completed work is not enough: we want to measure what percentage of what we do is planned, and how much is spontaneous or reactive by definition.

Epic filtering

Our definition of epic is very granular. Any action that impacts a customer is an epic, and we create separate epics for separate channels. For example, if I republish this article with slight changes in Medium or the Atlassian Community, then I will create three separate epics.

This means that our sprints regularly contribute to 50+ epics. We need a good system of labels and quick filters in order to be able to navigate through them in our planning sessions and make sure that we don’t oversee any important details.

Impact evaluation

We pride ourselves on having one of the best Google Analytics implementations in the Atlassian Ecosystem, and we want to make sure that we track the impact and success of every campaign. But at the same time, we still haven’t adopted the right process.

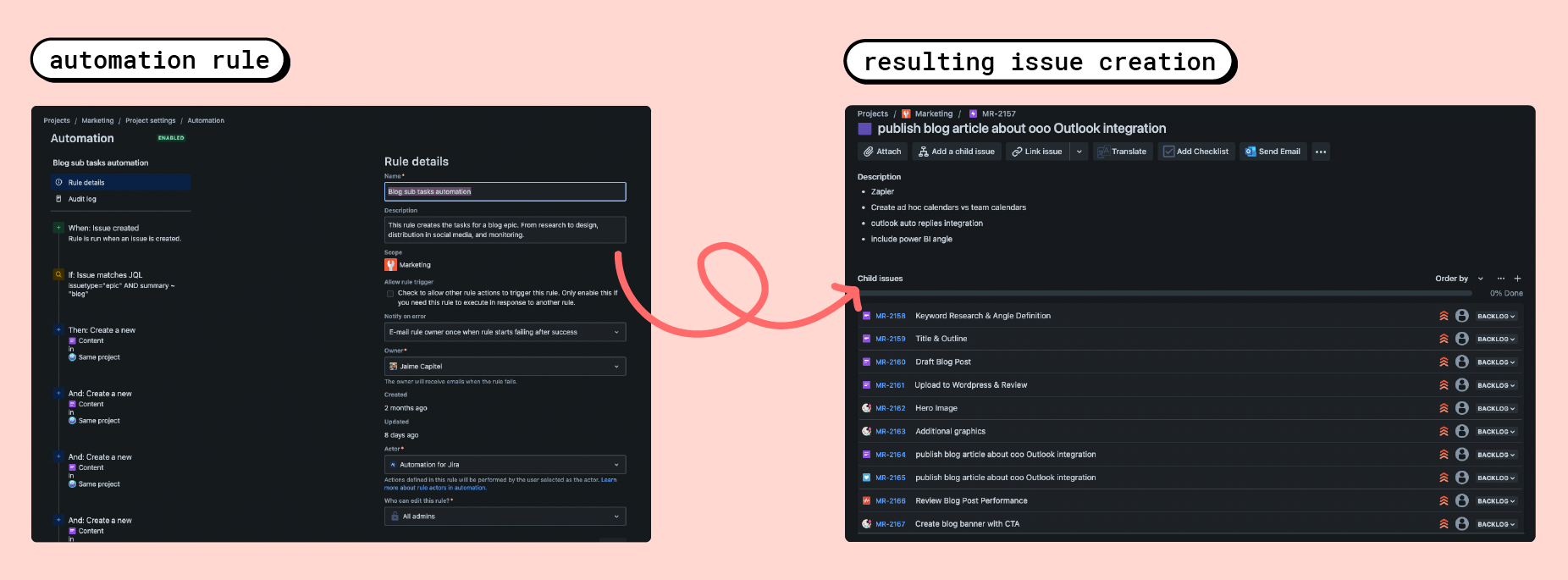

Automations

While we already rely on solid automations, like the one I have in place to automatically populate content epics, we still need to make progress and reach a state where we don’t forget to enter relevant data manually in Jira that will be needed later for our monitoring.

What are other teams doing?

But how were we going to decide what was the best workflow for each team? And how could we ensure that every team aligned to the rest and, at the same time, maintained its autonomy?

It seemed like the time was ripe for some external help.

In the next article we will see the impact of having an external consultant for running the 4-day week experiment, and how the rest of the teams prepared for the implementation thanks to her.